SERMON: The Debonair Disciple

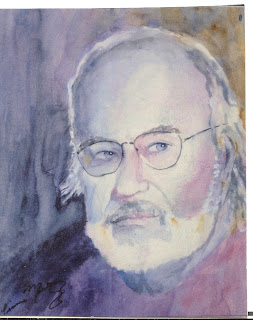

The Rev. Dana Prom Smith, S.T.D., Ph.D. (5/27/07)

Text: Matthew 5:1-10

The other day at a dinner party, a friend asked me, “Do you mind if I ask you a theological question?” I said, “Not at all,” politely lying for fear I was about to be put on the spot. People often suspect that ministers are a little dull and try to set them up with difficult theological questions, such as predestination to which the answer of simple. In the encounters between God and man, God initiates. A real no brainer, or else a totem.

The friend said, “What is your definition of God?” I replied, “If I were to define God, I would be committing a deicide and creating a totem instead. God cannot be confined within the limitations of a human proposition. A defined God is either an oxymoron or an idol.”

Isaiah speaks derisively of the Babylonians chaining down their gods so that they can’t be stolen. “To whom then will you liken God, or what likeness compare with him? The idol! A workman casts it, and a goldsmith overlays it with gold, and casts for it silver chains. He seeks out a craftsman to set up an image that will not move.” And then he asks, “To whom then will you compare” God? There is nice word for the incomprehensibility of God, mystery, that whom we experience and is yet beyond our comprehension.

Faith is not a concept or an idea, least of all, a definition. As Martin Buber, the famous Jewish theologian said, faith is an experience, an experience in which people understand themselves. He told the story of Rabbi Susya to make his point. Rabbi Susya was elderly, frail, and in ill health. His friends teased him that at the Last Judgment God would accuse him of not being more like Moses. He replied, “No, you are wrong, it would be that I was not more like Susya.”

In other words, the experience of God’s presence is about our authenticity and integrity, not about trying to be someone else. Alfred North Whitehead, the great British-American mathematician and philosopher and author with Bertrand Russell of Principia Mathematica, wrote that religion is what people do with their solitariness, when there is nothing but themselves, no supports, no illusions, no pretenses, the lies we tell and believe. Jean Paul Sartre’s phrase for those lies is “mauvais foi,” bad faith.

Martin Buber’s point was that in understanding ourselves we begin with that solitariness where no creed, canon law, church, ideology, state, or corporation can subdue us into being someone we are not. In short, in God’s presence we are free to be ourselves. Buber’s phrase for this divine-human encounter was I-Thou, when we come of spiritual age.

We do not speak about God, but rather our relationship with God. Theology, or Godtalk, is really talk about ourselves. Even in our human experiences, we don’t know someone else, but rather how we experience that person. I knew my father as a father. I never knew him in himself as himself. As a pastor and psychotherapist, I realized that I never really knew anyone else inside them as they were. All I knew was how they appeared to me. I’m sure many of us have had the experience of a counselor imposing a definition or diagnosis on us in a way that didn’t fit us deep inside. By the way, this is why diagnosis is always an on-going activity because good counselors are never sure they’re right, just as doubt is integral to faith.

The Beatitudes of Jesus are guides to that that I-Thou experience. It is important to understand that the Beatitudes are a Hebrew poem. Hebrew poetry did not use rhyme, rhythm, or meter as does English poetry. Being a highly inflected language, that is, a phrase is usually contained within one word, such as, “In the beginning” is one word as is “and the earth.” The Hebrew poetic style was parallelism, setting units of thought or phrases in parallels. For instance in the 23rd Psalm it reads, “He maketh me to lie down in green pastures” with a parallel line following “He leadeth me besides the still waters.” The second line restates the first, and then a third line concludes with “He restoreth my soul.” Very powerful poetry.

The Beatitudes are a poem of eight lines in which each one re-enforces the others. It consists of two quatrains. The first quatrain speaks of our experience of God and the second of our experience of the world. This morning I would like to focus on the first quatrain of our experience of God.

The Beatitudes describe a spiritual process, using the indicative mood, rather than the commanding imperative. In short, they are not commands, but rather descriptions. Each of the Beatitudes begins with the word “Blessed” which means fortunate or happy.

The first Beatitude reads, “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of God.” Jesus is describing a poverty of conviction. So much of what people believe is unnecessary and cumbersome. A lot of religious belief is tied up with the church and the church’s dogma. Many believers are burdened with an excessive baggage of doctrine and protocols. Some times they end up with “stuffed and stopped-up brains,” to use Robert Browning’s words.

Many years ago when I was taking an airplane from Los Angeles to Bishop to backpack the High Sierra, I happened by a couple in the airport who were surrounded by ten or twelve pieces of very expensive luggage. Helpless in their excess, they were waiting for a Redcap to rescue them. The women pointed to me and said, “Look at that poor man. All that he has is on his back.” Being believers and practitioners of excess, they were disabled and trapped. This is to the point of spiritual poverty. It is not the humility the church teaches to manipulate the faithful. It is the simplicity of solitude, believing only what is necessary to believe. Goethe’s remedy is clear, “The last and greatest art is to limit and isolate oneself.”

One of my favorite college courses was on medieval philosophy, and especially two men, William of Occam and Nicolas de Cusa and his coincidentia oppositorum which means ‘Don’t get trapped by either-or arguments.” William of Occam made the point that one should not multiply ideas beyond necessity. It’s called the Principle of Parsimony. Keep it simple. The first Beatitude is something on the order of a spiritual principle of parsimony. Simplicity and economy mean lighter journeys. The more we believe in terms of content, the less we experience, the less life is allowed to filter through our excessive doctrines into our consciousness. Jesus promises the kingdom of heaven as a result of that simplicity, an opening to God’s varied wonders.

The next beatitude reads, “Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.” The word “mourn” here means a mourning of past sorrows which is a way of not dragging around the baggage of the past. One thing I learned in backpacking was to keep one’s pack as light as possible. Mourning is more than grief, that necessary sadness at loss, it is working through that loss to the other side. It is enough to learn from the past, not haul it around. It’s a way of dumping our karma. We are more than the accumulations of the past. We are also our hopes and dreams which can only come to pass if we leach ourselves of the debilitating messages of the past.

Many people carry around issues generated in the past. Years ago I officiated at the funeral of an elderly woman who had been active in the church and various social causes in the community. Her husband refused to come to the service. He hated the church because his father forced him to attend church services. He had issues which debilitated him and kept him from the immediate.

Marshall McLuhan wrote about living through the rear-view mirror rather than the windshield. While it’s important to check the past’s rear-view mirror now and then to remember from whence we have come and who might be catching up with us, to use Satchel Page’s phrase, our attention is better spent on where we are going to avoid running into a tree.

The key is, of course, forgiveness, not only of others, but, more to the point, also of ourselves. This is especially poignant for people who’ve been victimized. Many define themselves as victims for a lifetime. The most effective way to rid oneself of victimization is to relive the experience not as a victim but as a victor. We can move from the roles of victims, to survivors, to prevailers, and finally to pilgrims. Ridding ourselves of the ravages of the past is spiritually efficient. The promise of this cleansing is comfort which in the biblical sense means being strengthened. It is akin to the relief of a released burden, a feeling of lightness, a renewal of energy.

The next beatitude is “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.” In some ways this is the most intriguing. The word for meek in Greek is πραΰς (praues) which was used for the training of race horses, Olympic athletes, and the aristocracy. The French translate it, “débonnaire.” When Queen Elizabeth visited Jamaica some years ago, the crowd often shouted, “She meek. She so meek.” The Jamaicans speak a dialect of English not far from Elizabethan, the time of the King James Version.

Meek meant gentle, as in gentleman and gentlewoman, and in gentling a horse. Breeding out the wild and focusing the energy, making the person or animal more morally graceful and efficient.

A great athlete makes it look effortless and graceful because there’s no wasted motion. It is simple, uncluttered, and unencumbered. Of course, the word is discipline. All the energy is devoted to the task, an effortless grace, unencumbered by excessive ideology, past grievances, trivial pursuits.

Accomplishing our lives with grace requires discipline, the ability to get rid of those things that really don’t matter. Robert Browning’s “less is more” is to the point. Even in writing, it is important to keep it lean. A simple “I love you” is more powerful than “I really love you a lot.”

One of my nephews was a major league pitcher. He said the first thing he had to learn was to “keep my eye on the ball rather than the stands.”

Each beatitude re-enforces the other. The simplicity of the poor in spirit, the freedom of having mourned the past, and the discipline of ridding oneself of life’s sideshows are part and parcel of spiritual integrity and authenticity.

The last beatitude in the quatrain is “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied.” While it may surprise many of you, righteousness does not mean doing right, it means the graciousness of God in the Old Testament Hebrew. God’s righteousness meant God’s grace. We even pick it up in our daily speech, as in “it’s the righteous thing to do.”

In terms of morals, there are at least two kinds, reactive and active. Reactive is the anti-vice morality of not doing the wrong things, such as getting drunk, stealing, adultery, discriminating racially, homophobia, etc. Reactive morality has a vindictive quality, while active morality is graceful, doing justice and loving mercy. It is doing something rather than not doing something. Righteousness is the active morality of justice and mercy, that is, actually reaching out to help someone else.

Hungering and thirsting are fundamental human experiences on the order of spiritual simplicity, freedom from past grievances, and discipline. As W. N. Murray wrote in The Scottish Himalayan Expedition 1951, “Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness.” So it is with hungering and thirsting for justice and mercy, a life of grace. Think of all the hesitancies created by excessive ideologies, conflicted values, past grievances, irrelevant concerns that have kept us from moving forward.

The promise is satisfaction, a world opening up. The word for sin in the New Testament is ‛αμαρτία (hamartia), missing the target. An archers term, it means a life of irrelevance, of missing the point, or frittering away one’s life. Hungering and thirsting means staying on point, keeping your eye on the ball, going somewhere worthwhile.

John Bunyan was right. Our lives are a Pilgrim’s Progress. We need to travel light, not lug the past, keep focused, and stick to our destiny which is a life of righteousness, a life of grace. Amen

Copyright © Dana Prom Smith 2007